Linearly interpolating functions

A common bottle-neck in computing often lies with evaluating computationally intensive functions. There are many ways to approximate functions which give speed improvements. This document discusses a possible improvement to linear interpolation using a lookup table.

Best-fit piecewise linear function

The basic idea is that we want to estimate $f(x)$ with a piecewise linear function $g(x)$. It is defined by pairs $(x_i, y_i)$ for $i = 0, 1, \ldots, N$ as

\begin{gather} g(x) = (y_{i+1} - y_i) \frac{x - x_i}{x_{i+1} - x_i} + y_i \quad \text{for} \quad x \in [x_i, x_{i+1}) . \tag{1}\label{eq:linear_interp} \end{gather}

For the lookup table to have constant lookup time, we choose to have the $x$ values equally spaced,

\begin{gather} x_i = x_0 + i \Delta x , \tag{2} \end{gather}

and so given a value $x$, the range $[x_i, x_{i+1})$ it falls in can be found by

\begin{gather} i(x) = \mathrm{floor}\left(\frac{x - x_0}{\Delta x}\right) . \tag{3} \end{gather}

Therefore, the linearly interpolated approximation $g(x)$ to the function $f(x)$ is given by \eqref{eq:linear_interp} for $i = i(x)$. This approximation is valid for the whole range $[x_0, x_N)$.

Since the points $x_i$ are fixed, the problem then becomes how to define the set $y_i$ that best fits the function $f(x)$. The simplest approach is just to use $y_i = f(x_i)$, but this underestimates the function when it is concave down, and overestimates it when it is concave up. We want an unbiased estimation that minimizes the error

\begin{gather} e(\mathbf{y}) = \int_{x_0}^{x_N} \mathrm{d}x\, (f(x) - g(x,\mathbf{y}))^2 , \tag{4}\label{eq:error} \end{gather}

where we made the dependence on the variables $\mathbf{y}$ explicit in the approximation function $g$. To have continuity with the original function, we let $y_0 = f(x_0)$ and $y_N = f(x_N)$, and so this is a minimization problem over the $N-1$ variables $y_1, y_2, \ldots, y_{N-1}$.

Determining optimal points $\mathbf{y}$

The goal is to select $\mathbf{y}$ that minimizes the error \eqref{eq:error}. This is satisfied under the following condition:

\begin{gather} \partial_i e(\mathbf{y}) = -2 \int_{x_0}^{x_N} \mathrm{d}x\, \partial_i g(x, \mathbf{y}) (f(x) - g(x,\mathbf{y})) = 0 . \tag{5}\label{eq:grad} \end{gather}

Since $g(x)$ is piecewise linear (equation \eqref{eq:linear_interp}), it can be re-written as (where $\theta$ is the Heaviside step function)

\begin{gather} g(x, \mathbf{y}) = \sum_{i = 0}^{N-1} (\theta(x - x_{i}) - \theta(x - x_{i+1})) \left( (y_{i+1} - y_i) \frac{x - x_i}{\Delta x} + y_i \right) . \tag{6} \end{gather}

It has partial derivative with respect to $y_i$ for $i = 1, 2, \ldots, N-1$,

\begin{align} \partial_i g(x, \mathbf{y}) & = \sum_{j = 0}^{N-1} (\theta(x - x_{j}) - \theta(x - x_{j+1})) \left( \delta_{i,j+1} \frac{x - x_j}{\Delta x} + \delta_{i,j} (1 - \frac{x - x_j}{\Delta x}) \right) , \tag{7} \end{align} \begin{align} & = (\theta(x - x_{i-1}) - \theta(x - x_{i})) \frac{x - x_{i-1}}{\Delta x} + (\theta(x - x_{i}) - \theta(x - x_{i+1})) (1 - \frac{x - x_{i}}{\Delta x}) . \tag{8} \end{align}

Substituting this into the condition \eqref{eq:grad} gives, for $i = 1, 2, \ldots, N-1$,

\begin{gather} \int_{x_{i-1}}^{x_i} \mathrm{d}x\, \frac{x - x_{i-1}}{\Delta x} (f(x) - g(x,\mathbf{y})) + \int_{x_{i}}^{x_{i+1}} \mathrm{d}x\, \frac{x_{i+1} - x}{\Delta x} (f(x) - g(x,\mathbf{y})) = 0 . \tag{9}\label{eq:grad2} \end{gather}

This can be re-written as

\begin{gather} \int_{0}^{\Delta x} \mathrm{d}\alpha\, \frac{\alpha}{\Delta x} (f(x_{i-1} + \alpha) + f(x_{i+1} - \alpha) - g(x_{i-1} + \alpha, \mathbf{y}) - g(x_{i+1} - \alpha, \mathbf{y})) = 0. \tag{10}\label{eq:grad3} \end{gather}

The $f$ terms integrate to a constant,

\begin{gather} F_i = \int_{0}^{\Delta x} \mathrm{d}\alpha\, \frac{\alpha}{\Delta x} (f(x_{i-1} + \alpha) + f(x_{i+1} - \alpha)) . \label{eq:F} \tag{11} \end{gather}

Using the definition \eqref{eq:linear_interp}, the $g$ terms become

\begin{gather} \int_{0}^{\Delta x} \mathrm{d}\alpha\, \frac{\alpha}{\Delta x} (g(x_{i-1} + \alpha) + g(x_{i+1} - \alpha)) \tag{12} \end{gather} \begin{gather} = \int_0^{\Delta x} \mathrm{d}\alpha\, \frac{\alpha}{\Delta x} \left(\frac{\alpha}{\Delta x} (2 y_i - y_{i-1} - y_{i+1}) + y_{i+1} + y_{i-1}\right) \tag{13} \end{gather} \begin{gather} = \Delta x \int_0^{1} \mathrm{d}\beta\, \beta^2 (2 y_i - y_{i-1} - y_{i+1}) + \beta (y_{i+1} + y_{i-1}) \tag{14} \end{gather} \begin{gather} = \frac{\Delta x}{6} (y_{i-1} + 4 y_i + y_{i+1}) \label{eq:G} . \tag{15} \end{gather}

This equation \eqref{eq:grad3} can now be written in the form

\begin{gather} m_{i,i-1} \ y_{i-1} + m_{i,i} \ y_i + m_{i,i+1} \ y_{i+1} = F_i , \tag{16} \end{gather}

where

\begin{align} m_{i,i-1} & = \Delta x / 6 , \quad m_{i,i} & = 2 \Delta x / 3 , \quad m_{i,i+1} & = \Delta x / 6 . \tag{17} \end{align}

This forms a linear system of equations $M^\prime \mathbf{y}^\prime = \mathbf{C}^\prime$, where $M^\prime$ is a $(N-1) \times (N+1)$ matrix, $\mathbf{y}^\prime$ is the vector $(y_0, y_1, \ldots, y_N)$, and $\mathbf{C}^\prime$ is a length $N-1$ vector given by elements $F_i$. The first and last components of $\mathbf{y}^\prime$ are constants, and the only non-zero elements of $M^\prime$ in the first and last columns are $M^\prime_{1,0}$ and $M^\prime_{N-1,N}$, so this can be reduced to a system of $N-1$ equations

\begin{gather} M \mathbf{y} = \mathbf{C} , \tag{18} \end{gather}

where $M$ is the $(N-1)\times(N-1)$ submatrix of $M^\prime$, $C_1 = C^\prime_1 - y_0 M^\prime_{1,0}$, $C_{N-1} = C^\prime_{N-1} - y_N M^\prime_{N-1,N}$, and $C_i = C^\prime_i$ otherwise. The solution is then given as

\begin{gather} \mathbf{y} = M^{-1} \mathbf{C} . \tag{19} \end{gather}

These points $y_i$ determine the piecewise linear function \eqref{eq:linear_interp} that minimizes the error \eqref{eq:error}. The problem is now reduced to inverting a tridiagonal matrix.

Inverting tridiagonal matrix $M$

The basic technique for inverting a tridiagonal matrix can be found on Wikipedia here. Let $n = N-1$, so $M$ is a $n\times n$ matrix, and also $\delta = \Delta x / 6$. Using the notation at the Wikipedia link, $a_i = 4\delta$, and $b_i = c_i = \delta$. The inverse matrix is entirely determined by coefficients $\theta_i$ for $i$ from 0 to $n$, and $\phi_i$ for $i$ from 1 to $n+1$, and these have their own recurrence relation. I will skip some of the details, but the first thing to note is that the symmetry of the matrix means $\phi_{n+1-i} = \theta_i$ and $\phi_i = \theta_{n+1-i}$. Writing $\theta_i = k_i \delta^i$, the $k$ coefficients satisfy the recurrence relation

\begin{gather} k_i - 4k_{i-1} + k_{i-2} = 0 . \tag{20} \end{gather}

Writing $k_i = l_1 r_1^i + l_2 r_2^i$, then using the recurrence relation, solving the quadratic equation, and using the initial conditions gives the roots $r_1 = 2 + \sqrt{3}$ and $r_2 = 2 - \sqrt{3}$, so that

\begin{gather} k_i = \frac{r_1^{i+1}}{2\sqrt{3}} - \frac{r_2^{i+1}}{2\sqrt{3}} . \tag{21} \end{gather}

Substituting the values for $\theta_i$ and $\phi_i$ into the equation for the inverse on Wikipedia, many things cancel, and when the dust settles the elements are

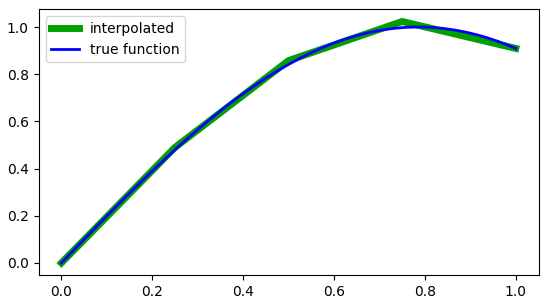

\[(M^{-1})_{ij} = \frac{(-1)^{i+j}}{\delta} \frac{k_{min(i,j)-1} k_{n-max(i,j)}}{k_n} . \tag{22}\]Here is an example of this algorithm applied to the function $\sin(2x)$ with 5 points. Notice how the green linearly fit function tends to pass through the center of the blue original function due to our choice of error function \eqref{eq:error}.

|

Benchmark

To demonstrate the effectiveness of this algorithm in speeding up calculation of transcendental functions, I wrote a simple bit of benchmark code that can be found here.

It compares calling std::sin to my custom defined fast_sin method defined using the above algorithm for 90 points between 0 and $2\pi$.

The benchmark runs for 10,000,000 values between $-\pi$ and $3\pi$, and also computes the maximum absolute error between the two functions.

The results I get from that online code sample is

1

2

3

std::sin, sum 9.7525e-05, time per call (ns): 59.9636

fast_sin, sum 9.74093e-05, time per call (ns): 19.9605

max absolute error: 0.000386341

Here the fast_sin method is 3 times faster.

Also, the largest absolute error is 0.00038, and considering that the range of sin is from -1 to 1, this is fairly small.

I am not sure what compile flags that site uses, so I also tested locally and found the same 3 times speed up:

1

2

3

4

5

➜ cpp clang++ -std=c++11 -Ofast -O3 super_linear.cpp -o super_linear

➜ cpp ./super_linear

std::sin, sum 9.7525e-05, time per call (ns): 27.1848

fast_sin, sum 9.74093e-05, time per call (ns): 9.48272

max absolute error: 0.000386341