Google foobar challenge

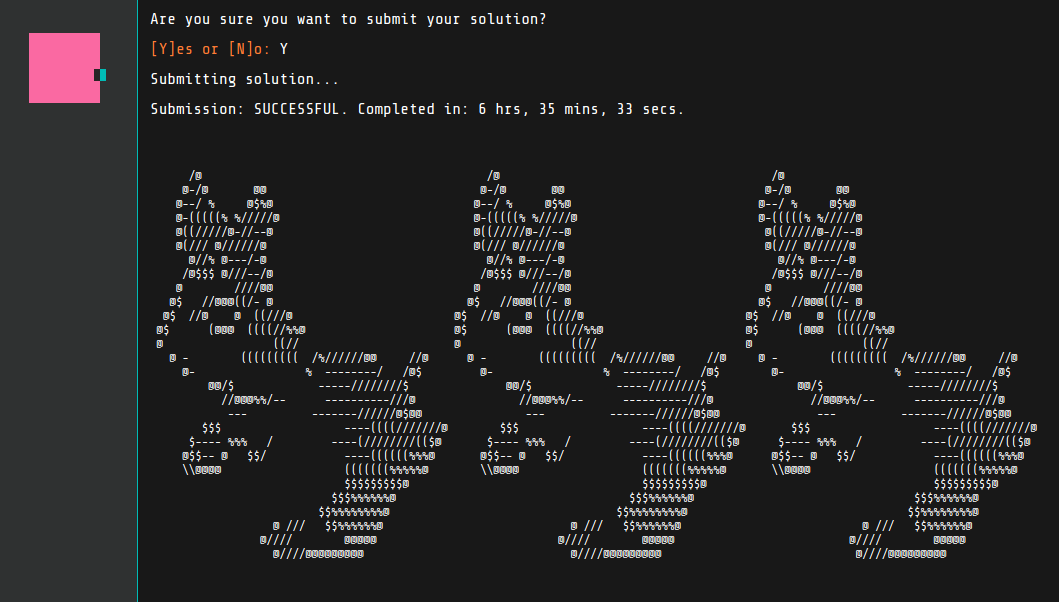

I recently came across the Google foo.bar challenge during work a few days ago. I had been doing Google searches on various programming topics when an invitation to take the challenge popped up. It was my first time even hearing about it. For those who don’t know, it seems that this is a secret process carried out by Google for recruiting developers. There are 5 levels of challenges that can be overcome, some levels consisting of more than one programming challenge. After completing level 3, you get the opportunity to submit your contact information, which may be used by Google recruiters to contact you. Each challenge you accept has a certain time limit. I cannot recall the exact limits, but early challenges were on the order of a few days, while level 4 was around 2 weeks for each challenge and the level 5 challenge was around 3 weeks.

I managed to power through to the end of level 5 over the last couple days, and would like to share some mathematical concepts that were required to complete level 5 that I enjoyed thinking about. The level 5 challenge can be defined as follows. Consider the set of $m \times n$ matrices with elements in $\mathbb{Z}_s$, which is denoted $\mathbb{Z}_s^{m \times n}$ (often will be referred to as $X$). Two matrices $A$ and $B$ in this set are considered equivalent if it is possible to transform $A$ into $B$ using any set of row and column swaps. For example, swapping the two rows and the first two columns of the left hand side here transforms it into the right hand side, so these matrices would be considered equivalent:

\begin{equation} \begin{pmatrix} 1 & 0 & 0 \\ 1 & 0 & 2 \end{pmatrix} \sim \begin{pmatrix} 0 & 1 & 2 \\ 0 & 1 & 0 \end{pmatrix} . \end{equation}

The goal is to define a function $N(m,n,s)$ that counts the number of equivalency classes of $X$ under the above equivalence relation (i.e. the number of unique matrices under this equivalence).

Doing a brute force search and count of this whole space would be an astronomically inefficient approach, partly because the number of total possible matrices is $|\mathbb{Z}_s^{m \times n}| = s^{mn}$. So instead it is necessary to use some mathematical machinery to cut right to the heart of this problem. The key tool used in the solution will be Burnside’s lemma.

Before we actually use Burnside’s lemma, let’s look at this specific problem a little more. Consider first just row swaps. Using permutation cycle notation, swapping row 1 and 2 is represented by $(1\ 2)$, and we have at our disposal all permutations $(i\ \ i+1)$ for $i \in \mathbb{Z}_{m-1}$. This generates the entire symmetric group $S_m$. Similarly, column swaps generate the whole symmetric group $S_n$.

Next, it can be seen that row swaps and column swaps are mutually commutative operations. You can do either row swaps first then column swaps, or the other way around and it does not matter. To see this, take $A \in X$, $\sigma_1 \in S_m$ and $\sigma_2 \in S_n$. The $(i,j)$ element of this matrix is taken to position $(\sigma_1(i), \sigma_2(j))$, which clearly is independent of the order of row/column permutations. This means that the group of all possible row and column permutations is given by simply the Cartesian product $G = S_m \times S_n$.

The group action of elements in $G$ on the set $X$ is given by $\varphi : G \times X \rightarrow X$ canonically as follows. For $g = \sigma_1 \times \sigma_2 \in G$ the map $\varphi(g, M)$ for $M \in X$ is equal to $M$ after application of row permutation $\sigma_1$ and column permutation $\sigma_2$.

Going back to the problem at hand, we are trying to count the equivalency classes of $X$ under action by $G$, which is $X / G$. According to Burnside’s lemma, this means that the answer we seek is

\[N(m,n,s) = |\mathbb{Z}_{s}^{m \times n} / S_{m} \times S_n| = |X / G| = \frac{1}{|G|} \sum_{g \in G} |X^g| \tag{1}\label{eq:n}\]Since $|G| = m!\ n!$, we just need to find the size of $X^g$ which is the set of points fixed by $g$, $\{x \in X | g \cdot x = x\}$. To do that, let us look at elements of the group $G = S_m \times S_n$ in more detail.

Any permutation $\sigma \in S_n$ can be written using cycle notation. In this notation, the specific order of the cycles does not matter. This permutation belongs to some conjugacy class which is uniquely determined by Young diagrams of size $n$, $Y_n$ (the unique partitioning of positive integers that sum to $n$). To see why conjugacy classes preserve cycle structure, see here. As an example, if $n=5$ and the permutation is $(1 2 3)(4 5)$, then this is a member of the conjugacy class consisting of all 3-cycles and 2-cycles, and can for instance be transformed into $(1 2 4)(3 5)$ by conjugating with element $(3 4)$. This conjugacy class is represented by the Young diagram with row lengths $[3, 2]$.

We will compute the sum in $\eqref{eq:n}$ by summing over the conjugacy classes of $G$, making sure to multiply by the appropriate symmetry factor. All $g \in G$ have a conjugacy class represented by Young diagrams $y_1 \in Y_m$ and $y_2 \in Y_n$, and we would like to count the number of elements in $X^g$ for each group element $g$. Since we only care about the conjugacy class, we can consider any representative element out of this conjugacy class we desire. In particular, we can choose a canonical form where larger cycles are written first, and the numbers are increasing. For instance, $y = [3,1,1]$ would have representative element $(1 2 3) (4) (5)$, and $y = [2, 2, 1]$ would have $(1 2) (3 4) (5)$.

Now, before counting elements in $X^g$ let us look at a specific example to get some intuition. If we have $m=3$ and $n=5$, with $y_1 = [2,1]$ and $y_2 = [3,2]$, then the row/column permutations are given by $(1 2) (3)$ and $(1 2 3) (4 5)$. This breaks the $3 \times 5$ matrix up into 4 sub-squares of sizes $2 \times 3$, $2 \times 2$, $1 \times 3$, and $1 \times 2$ that are independently mixed up by the permutations:

\begin{equation} \left(\begin{array}{ccc|cc} \cdot & \cdot & \cdot & \cdot & \cdot \\ \cdot & \cdot & \cdot & \cdot & \cdot \\ \hline \cdot & \cdot & \cdot & \cdot & \cdot \end{array}\right) \end{equation}

So to count the elements of $X^g$ (the elements that are not changed by permutation $g$), we just have to count all the ways we can put the numbers 1 through $s$ into this matrix such that the above row/column permutations does not change it.

To count this, we have to look at the orbits within each $k \times l$ sub-problem. The top left box here is $2 \times 3$. Successive applications of $g$ generates the following orbit: $(1,1)$, $(2,2)$, $(1,3)$, $(2,1)$, $(1,2)$, $(2,3)$, and back to the start $(1,1)$. This orbit spans the entire sub-box, and so we can only safely put in a single number and have it be unchanged under application of $g$. This box therefore contributes $s$ to $|X^g|$. The top right box is $2 \times 2$ and has two orbits, $(1,1)$ to $(2,2)$ and $(1,2)$ to $(2,1)$, and so there are two orbits to put numbers into that do not interfere with each other, and so this contributes $s^2$. Similarly, the bottom two boxes contribute $s$ and $s$, so we have $|X^g| = s^5$. For a general $k \times l$ box, the individual contribution is $s^{gcd(k,l)}$.

Let us put everything together now. The above arguments tell us that the size of the fixed points of $g$ is

\begin{gather} |X^{\sigma_{y_1} \times \sigma_{y_2}}| = s^{\sum_{i=1}^{|y_1|} \sum_{j=1}^{|y_2|} gcd(y_{1,i}, y_{2,j})} . \end{gather}

Here we are denoting the canonical permutation in the conjugacy class represented by the Young diagram $y$ as $\sigma_y$. Substituting that into equation $\eqref{eq:n}$ gives

\begin{gather} N(m,n,s) = \frac{1}{m! n!} \sum_{y_1 \in Y_m} \sum_{y_2 \in Y_n} C_{y_1} C_{y_2} s^{\sum_{i=1}^{|y_1|} \sum_{j=1}^{|y_2|} gcd(y_{1,i}, y_{2,j})} , \end{gather}

where the constant $C_{y}$ is the symmetry factor, the number of permutations that are a member of the conjugacy class for Young diagram $y$. To then complete the programming challenge, all one needs to do is find an efficient way to compute the set of Young diagrams $Y_n$, and to determine the symmetry factors $C_y$.